I recently researched the current state of efforts to address human trafficking and forced labor (herein referred to as human rights violations) in the global fisheries industry, efforts to promote sustainable fisheries, and synergies among them. The goal was to identify opportunities to develop a system solution to combat human rights and promote sustainable practices throughout the global fisheries industry – two very worthy causes.

The Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO) estimates that nearly 30 percent of global fish stocks are depleted, over-exploited or in recovery.

The extent of abuses and dismal conditions that human rights victims are subject to on fishing vessels are considered among the worst.

As many of you know, much of my work centers on developing or implementing systems to improve impacts or conditions of production (e.g. cotton, biofuels, conflict minerals) through complex supply chains and business realities. I often contend that the complexity of the supply chain increases with every new supply chain I encounter. Fisheries presents a new and somewhat daunting complexity because of the global scale of the origin (the world’s oceans, lakes, rivers and, increasingly, aquaculture) and the limited and largely uncoordinated monitoring and enforcement of international laws in much of the ocean. These factors combine to create a situation that is akin to the wild, wild west – lawless chaos.

With this lawless chaos, fisheries and workers suffer from the ripple effects of Illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing – fishing conducted in violation of national laws or internationally agreed upon conservation and management measures in oceans around the world. Experts estimate that IUU fishing accounts for up to a quarter of the world's total catch of wild fish.[1] There are often strong links between IUU fishing and overfishing as well as human rights violations, as the vessels may also be used for the purposes of smuggling migrants or trafficking in persons.[2] Tackling IUU fishing is central to combating human rights abuses and creating more sustainable fisheries.

The existing complex of legal frameworks, jurisdictions, and authorities creates a challenge to enforce international laws. Let me share a little of what I learned about this intricate framework and opportunities to address IUU fishing and associated human rights violations.

Maritime zones

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which was adopted in 1982, defines territories and authorities within different regions of ocean waters (maritime zones) as follows:

Territorial waters extend up to at most 12 nautical miles from the coast. The territorial sea is regarded as the sovereign territory of the state, with sovereignty extending to the seabed below.

Contiguous zones extend up to 12 nautical miles from the outer edge of the territorial waters (and up to 24 nautical miles from the coastline). A state can exert limited control within the contiguous zone to prevent or punish "infringement of its customs, fiscal, immigration or sanitary laws and regulations within its territory or territorial sea."[3]

Exclusive economic zones (EEZs) extend from the outer limit of the territorial waters to a maximum of 200 nautical miles from the coast, including the contiguous zone. A state has control of all economic resources within its EEZ, including fishing. Approximately 90 percent of fish captures take place in EEZs.[4]

High seas (also known as international waters) consist of oceans, seas, and waters beyond EEZs. Ships sailing the high seas are generally under the jurisdiction of the flag State (see below). Other nations can exercise jurisdiction when a ship is involved or suspected to be involved in certain criminal acts, including engaging in the slave trade.

Governing bodies and legal instruments

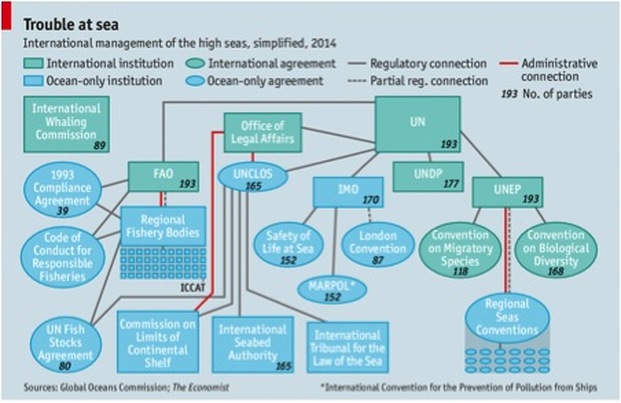

Several governing bodies monitor and act in fisheries. The International Maritime Organisation, International Labor Organization, and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Fisheries and Aquaculture Department lead efforts on the prevention of marine pollution, safety of fishers and fishing vessels, and fisheries management, respectively. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime, INTERPOL Fisheries Crime Working Group, and OECD High Seas Task Force address IUU fishing. Many conventions and international agreements that promote responsible fishing and legal activities in maritime industries are in place (see a few of them in figure below). Unfortunately, fishing vessels are exempt from many of these and other helpful instruments.

Enforcement authorities

Authorities responsible for enforcing international laws in these zones consist of flag States, port States, Regional Fisheries Bodies, and Regional Fisheries Management Organizations.

Flag States: Under UNCLOS, every country has the right to register ships and to permit them to fly their flag.[5] The flag State of a commercial vessel is the state under whose laws the vessel is registered or licensed. The flag State has primary responsibility for regulating vessel activities and enforcing laws on board fishing vessels.

Long distance fishing operators that are organized in transnational corporations can manipulate frameworks by registering their vessels in flag States that differ from that of the ship's owners and that do not properly enforce international laws. This practice is commonly called “flag of convenience.” Ships are often registered under flags of convenience to reduce operating costs or avoid the regulations of the owner's country.

Port States: Port State Control is responsible for the inspection of foreign ships in other national ports to ensure compliance with international safety laws and labor standards and to see that the vessel is manned and operated in compliance with applicable international law.

Regional Fisheries Bodies (RFBs): RFBs are instruments that enable states and organizations to work together to conserve, manage, and develop fisheries. RFBs can be Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs, see below), Advisory Bodies or Scientific Bodies. There are currently 44 RFBs worldwide, 20 of which are RFMOs.

Regional Fisheries Management Organizations: RFMOs are intergovernmental fisheries organizations that are responsible for managing fishery resources in a particular region of international waters or of highly migratory species (e.g. tunas, marlin, sailfish, sharks, swordfish). RFMOs are tasked with the inspection and management of documentation required of fishing vessels, employers, vessel operators, and owners, among other duties.

Registering and monitoring fishing vessels

Monitoring vessels and personnel on fishing vessels is a top priority to combat IUU and related criminal activities. Progress is being made to pressure commercial fishing boats (weighing over 1,000 gross tons) to obtain a Unique Vessel Identifier (UVI) system and to develop a Global Record of Fishing Vessels, Refrigerated Transport Vessels, and Supply Vessels (referred to as Global Record) to enter and track information about shipping vessels, better enabling entities to triangulate information and identify false claims or vessels and operators of concern. These systems would be invaluable in monitoring, controlling, and combating IUU fishing, human trafficking and forced labor, and improving sustainability in wild fisheries.

Market driven solutions

The European Union is currently the largest single market for imported fish and fishery products, representing 40 percent of total world imports.[6] The EU recently enacted a regulation to prevent, deter and eliminate IUU fishing. Its implementation has been effective, although there is some displacement of the issue (i.e. IUU fish) to the US and China. This regulation has also led RFMOs to implement stricter monitoring and control mechanisms to prevent IUU fishing and extensive human rights and labor abuses in their fishing grounds.

I believe major buyers in key markets (e.g. EU, US and Japan) will soon be more aware of the existence, scale, and threat that IUU activities pose to their – and the industry’s – business and reputation. With the leadership of major buyers, and involvement by all responsible members of the fisheries industry, I am hopeful we can expand existing systems and take a coordinated effort to combat these and other wrongs, despite the fisheries supply chain’s complexity and scale. After all, we are simply asking the key producers to respect international laws.

[1]Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch: Wild Seafood.

[2] Combating Transnational Organized Crime Committed at Sea, 2013.

[3] United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

[4] The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2010, pg. 94.

[5] Ships, Slaves and Competition, 2000, pg. 88.

[6] The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2010, pg. 16.

The Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO) estimates that nearly 30 percent of global fish stocks are depleted, over-exploited or in recovery.

The extent of abuses and dismal conditions that human rights victims are subject to on fishing vessels are considered among the worst.

As many of you know, much of my work centers on developing or implementing systems to improve impacts or conditions of production (e.g. cotton, biofuels, conflict minerals) through complex supply chains and business realities. I often contend that the complexity of the supply chain increases with every new supply chain I encounter. Fisheries presents a new and somewhat daunting complexity because of the global scale of the origin (the world’s oceans, lakes, rivers and, increasingly, aquaculture) and the limited and largely uncoordinated monitoring and enforcement of international laws in much of the ocean. These factors combine to create a situation that is akin to the wild, wild west – lawless chaos.

With this lawless chaos, fisheries and workers suffer from the ripple effects of Illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing – fishing conducted in violation of national laws or internationally agreed upon conservation and management measures in oceans around the world. Experts estimate that IUU fishing accounts for up to a quarter of the world's total catch of wild fish.[1] There are often strong links between IUU fishing and overfishing as well as human rights violations, as the vessels may also be used for the purposes of smuggling migrants or trafficking in persons.[2] Tackling IUU fishing is central to combating human rights abuses and creating more sustainable fisheries.

The existing complex of legal frameworks, jurisdictions, and authorities creates a challenge to enforce international laws. Let me share a little of what I learned about this intricate framework and opportunities to address IUU fishing and associated human rights violations.

Maritime zones

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which was adopted in 1982, defines territories and authorities within different regions of ocean waters (maritime zones) as follows:

Territorial waters extend up to at most 12 nautical miles from the coast. The territorial sea is regarded as the sovereign territory of the state, with sovereignty extending to the seabed below.

Contiguous zones extend up to 12 nautical miles from the outer edge of the territorial waters (and up to 24 nautical miles from the coastline). A state can exert limited control within the contiguous zone to prevent or punish "infringement of its customs, fiscal, immigration or sanitary laws and regulations within its territory or territorial sea."[3]

Exclusive economic zones (EEZs) extend from the outer limit of the territorial waters to a maximum of 200 nautical miles from the coast, including the contiguous zone. A state has control of all economic resources within its EEZ, including fishing. Approximately 90 percent of fish captures take place in EEZs.[4]

High seas (also known as international waters) consist of oceans, seas, and waters beyond EEZs. Ships sailing the high seas are generally under the jurisdiction of the flag State (see below). Other nations can exercise jurisdiction when a ship is involved or suspected to be involved in certain criminal acts, including engaging in the slave trade.

Governing bodies and legal instruments

Several governing bodies monitor and act in fisheries. The International Maritime Organisation, International Labor Organization, and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Fisheries and Aquaculture Department lead efforts on the prevention of marine pollution, safety of fishers and fishing vessels, and fisheries management, respectively. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime, INTERPOL Fisheries Crime Working Group, and OECD High Seas Task Force address IUU fishing. Many conventions and international agreements that promote responsible fishing and legal activities in maritime industries are in place (see a few of them in figure below). Unfortunately, fishing vessels are exempt from many of these and other helpful instruments.

Enforcement authorities

Authorities responsible for enforcing international laws in these zones consist of flag States, port States, Regional Fisheries Bodies, and Regional Fisheries Management Organizations.

Flag States: Under UNCLOS, every country has the right to register ships and to permit them to fly their flag.[5] The flag State of a commercial vessel is the state under whose laws the vessel is registered or licensed. The flag State has primary responsibility for regulating vessel activities and enforcing laws on board fishing vessels.

Long distance fishing operators that are organized in transnational corporations can manipulate frameworks by registering their vessels in flag States that differ from that of the ship's owners and that do not properly enforce international laws. This practice is commonly called “flag of convenience.” Ships are often registered under flags of convenience to reduce operating costs or avoid the regulations of the owner's country.

Port States: Port State Control is responsible for the inspection of foreign ships in other national ports to ensure compliance with international safety laws and labor standards and to see that the vessel is manned and operated in compliance with applicable international law.

Regional Fisheries Bodies (RFBs): RFBs are instruments that enable states and organizations to work together to conserve, manage, and develop fisheries. RFBs can be Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs, see below), Advisory Bodies or Scientific Bodies. There are currently 44 RFBs worldwide, 20 of which are RFMOs.

Regional Fisheries Management Organizations: RFMOs are intergovernmental fisheries organizations that are responsible for managing fishery resources in a particular region of international waters or of highly migratory species (e.g. tunas, marlin, sailfish, sharks, swordfish). RFMOs are tasked with the inspection and management of documentation required of fishing vessels, employers, vessel operators, and owners, among other duties.

Registering and monitoring fishing vessels

Monitoring vessels and personnel on fishing vessels is a top priority to combat IUU and related criminal activities. Progress is being made to pressure commercial fishing boats (weighing over 1,000 gross tons) to obtain a Unique Vessel Identifier (UVI) system and to develop a Global Record of Fishing Vessels, Refrigerated Transport Vessels, and Supply Vessels (referred to as Global Record) to enter and track information about shipping vessels, better enabling entities to triangulate information and identify false claims or vessels and operators of concern. These systems would be invaluable in monitoring, controlling, and combating IUU fishing, human trafficking and forced labor, and improving sustainability in wild fisheries.

Market driven solutions

The European Union is currently the largest single market for imported fish and fishery products, representing 40 percent of total world imports.[6] The EU recently enacted a regulation to prevent, deter and eliminate IUU fishing. Its implementation has been effective, although there is some displacement of the issue (i.e. IUU fish) to the US and China. This regulation has also led RFMOs to implement stricter monitoring and control mechanisms to prevent IUU fishing and extensive human rights and labor abuses in their fishing grounds.

I believe major buyers in key markets (e.g. EU, US and Japan) will soon be more aware of the existence, scale, and threat that IUU activities pose to their – and the industry’s – business and reputation. With the leadership of major buyers, and involvement by all responsible members of the fisheries industry, I am hopeful we can expand existing systems and take a coordinated effort to combat these and other wrongs, despite the fisheries supply chain’s complexity and scale. After all, we are simply asking the key producers to respect international laws.

[1]Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch: Wild Seafood.

[2] Combating Transnational Organized Crime Committed at Sea, 2013.

[3] United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

[4] The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2010, pg. 94.

[5] Ships, Slaves and Competition, 2000, pg. 88.

[6] The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2010, pg. 16.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed