Earlier this year, my colleague shared an issue paper that provides background on and objectives of The European Commission’s (the Commission’s) new strategic approach on Strengthening the Role of the Private Sector in Achieving Inclusive and Sustainable Growth in Developing Countries. The Commission believes that a new approach to private sector engagement is needed to meet current development agendas because partnerships between the private and public sectors can have a greater collective impact in developing countries than each sector working separately can.

The European Union (EU) is the largest donor of development aid worldwide. In 2010, the EU provided €53.8 billion – more than 50 percent of global aid. The Commission is the second largest donor globally, managing €11 billion of aid per year. As such a large donor of development aid worldwide, the EU is invested in ensuring that the funds are as effective as possible in this changing world.

The Commission aims to support the EU’s Agenda for Change, which focuses on new ways of engaging private sector partners through a blending of funds (e.g. loans and grants) to achieve sustainable growth in two priority areas:

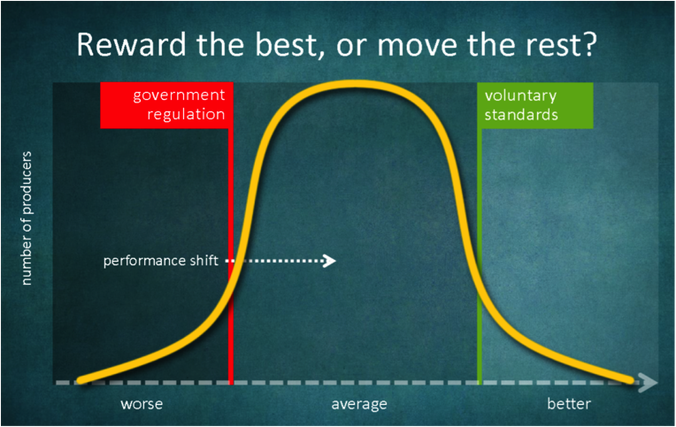

Figure 1: Shifting the bulk of an industry towards improved performance

The Commission proposed that its private partnership strategy will focus on the following top priorities:

1. Business environment reforms: enhance effectiveness by improving the quality and prioritization of reforms that target regional and business needs.

2. Employment impact and poverty focus of private sector development support: promote crosscutting issues such as women entrepreneurship, youth employment, and decent work.

3. Support for micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs): support the creation of business opportunities and markets for local MSMEs.

4. Vocational training and capacity development: provide a greater voice to employers when developing occupational standards and training programs.

5. Access to finance: strengthen the capacity of international intermediaries and support regulatory framework reform and the development of financial infrastructure.

6. Private sector partnership: engage in public-private partnerships and explore innovative financial instruments.

7. Private sector as the “delivery channel” for development: consider the private sector’s ability to provide services that have traditionally come from the public sector.

8. Private sector contribution to inclusive growth: provide economic opportunities to the poor that allow for sustainable livelihoods.

9. Transformation towards a green economy: the private sector – a critical actor in the advancement of economic development, job creation, and poverty alleviation – should be guided by an appropriate framework.

10. The role and responsibility of the private sector in a post-2015 framework: an active economic strategy to reach these objectives including providing incentives for public-private sector to contribute to sustainable and inclusive growth.

I am encouraged that the Commission recognizes the importance of the private sector in achieving its development goals, and I largely agree with their priorities. With this said, I would encourage the Commission to consider the following realities to allow for wider support across the private sector.

If government wants to shift the bell curve in Figure 1, they must ensure that its “pushing power” is scalable and effective. Regulations must also demand better performance over time. Government regulations often have more effect than voluntary standards (“pulling power”) on businesses’ investments and activities. An example of this is the impact that the US conflict minerals legislation has had on spurring companies and supply chain actors to act quickly – and largely consistently – across entire industries.

The importance of good governance in developing countries is understated by the Commission. Good governance is an essential foundation for any successful program or system. No private or public entity should be expected to invest in a poorly governed state. Governments are in a better position and have a responsibility to promote good governance in developing countries. The Commission should emphasize the importance of good governance and take action to address it.

I support the Commission’s focus on MSMEs, an essential segment of the supply chain. The Commission must also recognize that MSMEs often have limited resources and resiliency, which means that they might possibly present the greatest opportunity for improvement if they are introduced and integrated into a global market. The Commission’s plan to create a platform to connect EU buyers with MSME suppliers is a good approach to facilitate these connections.

Governments should also play a role in providing safety nets for, and building the resiliency of, the most vulnerable members of society such as MSMEs and the poor. Ideally the governments of developing countries would provide this, but governments in consumer markets may also have to contribute to such needs.

Businesses can provide demand, know-how, and needed innovation. They can influence policy and help align suppliers towards such common goals as sustainable and inclusive growth. They can be more flexible, responding to changing conditions more quickly than governments can. This greater flexibility can provide a deeper level of resiliency to changing realities and markets.

However, many retailers or end buyers do not typically make capital and long-term investments, especially in indirect supply chains. They can commit to being a guaranteed buyer, providing value to the supplier (e.g. predictable and consistent income). This may be an area where the Commission’s desired financial “blending mechanisms” can be effective. For example, if a fledgling company needs capital, a business can commit to purchasing a product that could provide assurances to lenders and other investors, who in turn would be more likely to provide the capital. Such a ”blended” solution involving several mutually dependent parties is possible these days as longer-term partnerships are replacing transactional buyer-seller relationships.

Lastly, I believe the Commission should clearly identify what their measure of success will be, make sure that benefits are reaching the most vulnerable, and do their utmost to target investments that will become financially self-sustaining over time.

I hope the Commission’s efforts to align with and foster collaboration among private and public sectors to build a sustainable and inclusive economy are successful.

The European Union (EU) is the largest donor of development aid worldwide. In 2010, the EU provided €53.8 billion – more than 50 percent of global aid. The Commission is the second largest donor globally, managing €11 billion of aid per year. As such a large donor of development aid worldwide, the EU is invested in ensuring that the funds are as effective as possible in this changing world.

The Commission aims to support the EU’s Agenda for Change, which focuses on new ways of engaging private sector partners through a blending of funds (e.g. loans and grants) to achieve sustainable growth in two priority areas:

- Human rights, democracy, and other key elements of good governance

- Inclusive and sustainable growth for human development

Figure 1: Shifting the bulk of an industry towards improved performance

The Commission proposed that its private partnership strategy will focus on the following top priorities:

1. Business environment reforms: enhance effectiveness by improving the quality and prioritization of reforms that target regional and business needs.

2. Employment impact and poverty focus of private sector development support: promote crosscutting issues such as women entrepreneurship, youth employment, and decent work.

3. Support for micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs): support the creation of business opportunities and markets for local MSMEs.

4. Vocational training and capacity development: provide a greater voice to employers when developing occupational standards and training programs.

5. Access to finance: strengthen the capacity of international intermediaries and support regulatory framework reform and the development of financial infrastructure.

6. Private sector partnership: engage in public-private partnerships and explore innovative financial instruments.

7. Private sector as the “delivery channel” for development: consider the private sector’s ability to provide services that have traditionally come from the public sector.

8. Private sector contribution to inclusive growth: provide economic opportunities to the poor that allow for sustainable livelihoods.

9. Transformation towards a green economy: the private sector – a critical actor in the advancement of economic development, job creation, and poverty alleviation – should be guided by an appropriate framework.

10. The role and responsibility of the private sector in a post-2015 framework: an active economic strategy to reach these objectives including providing incentives for public-private sector to contribute to sustainable and inclusive growth.

I am encouraged that the Commission recognizes the importance of the private sector in achieving its development goals, and I largely agree with their priorities. With this said, I would encourage the Commission to consider the following realities to allow for wider support across the private sector.

If government wants to shift the bell curve in Figure 1, they must ensure that its “pushing power” is scalable and effective. Regulations must also demand better performance over time. Government regulations often have more effect than voluntary standards (“pulling power”) on businesses’ investments and activities. An example of this is the impact that the US conflict minerals legislation has had on spurring companies and supply chain actors to act quickly – and largely consistently – across entire industries.

The importance of good governance in developing countries is understated by the Commission. Good governance is an essential foundation for any successful program or system. No private or public entity should be expected to invest in a poorly governed state. Governments are in a better position and have a responsibility to promote good governance in developing countries. The Commission should emphasize the importance of good governance and take action to address it.

I support the Commission’s focus on MSMEs, an essential segment of the supply chain. The Commission must also recognize that MSMEs often have limited resources and resiliency, which means that they might possibly present the greatest opportunity for improvement if they are introduced and integrated into a global market. The Commission’s plan to create a platform to connect EU buyers with MSME suppliers is a good approach to facilitate these connections.

Governments should also play a role in providing safety nets for, and building the resiliency of, the most vulnerable members of society such as MSMEs and the poor. Ideally the governments of developing countries would provide this, but governments in consumer markets may also have to contribute to such needs.

Businesses can provide demand, know-how, and needed innovation. They can influence policy and help align suppliers towards such common goals as sustainable and inclusive growth. They can be more flexible, responding to changing conditions more quickly than governments can. This greater flexibility can provide a deeper level of resiliency to changing realities and markets.

However, many retailers or end buyers do not typically make capital and long-term investments, especially in indirect supply chains. They can commit to being a guaranteed buyer, providing value to the supplier (e.g. predictable and consistent income). This may be an area where the Commission’s desired financial “blending mechanisms” can be effective. For example, if a fledgling company needs capital, a business can commit to purchasing a product that could provide assurances to lenders and other investors, who in turn would be more likely to provide the capital. Such a ”blended” solution involving several mutually dependent parties is possible these days as longer-term partnerships are replacing transactional buyer-seller relationships.

Lastly, I believe the Commission should clearly identify what their measure of success will be, make sure that benefits are reaching the most vulnerable, and do their utmost to target investments that will become financially self-sustaining over time.

I hope the Commission’s efforts to align with and foster collaboration among private and public sectors to build a sustainable and inclusive economy are successful.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed