The last time the concentration of Earth's main greenhouse gas reached this mark, horses and camels lived in the high Arctic. Seas were at least 30 feet higher—at a level that today would inundate major cities around the world.

Many are calling this a “symbolic mark.” It is neither. This milestone is based on real measurements of real atmospheric changes. It is not a mark like the mile markers we see along an endless highway.

Why is the 400 ppm milestone so important? According to the U.S. Presidential Climate Action Project, we have to stabilize atmospheric CO2 at concentrations around ppm to avoid catastrophic impacts. Stabilizing carbon dioxide at 450 ppm by 2050 requires global emissions to decline by 60 percent overall (with an 80 percent reduction by industrialized countries). For more on the Presidential Climate Action Project’s position on emissions reductions, click here.

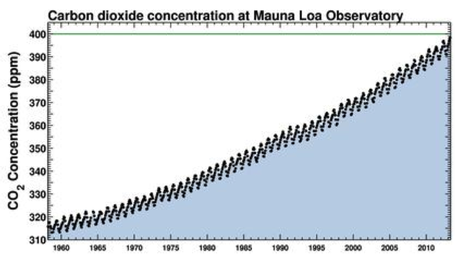

As you can see from the adjacent graph showing the levels of CO2 that have been observed at Mauna Loa, the longer-term trend is upward, and it is quickly approaching 450 ppm – the point at which global temperatures may begin to rise more than two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and result in catastrophic impacts.

There is reason for hope. According to an October 21, 2013 report by the U.S. Energy Information Administration, U.S. energy-related carbon dioxide emissions declined 3.8 percent in 2012. This change included a 5.1 percent decline in energy use per dollar of GDP as well as an increase in emissions on a per capita basis.

While these reductions are a strong start, they are not enough. Reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 60 to 80 percent requires large-scale solutions that can be mobilized in the very short-term.

We need appropriate policies, regulations and incentives from governments.

We need investments and innovation by private and public sectors, hopefully in a synergistic and collaborative manner. We also need companies and non-government organizations (NGOs) to reinvent themselves and their operating models to optimize the use of raw materials and drastically reduce GHG emissions.

NGOs have been important contributors towards the progress that has been made to date – raising awareness of issues to brands, consumers and industries, helping to set credible standards, and more. They are now working alongside industries and global brands. I think it would be wise for NGOs to reevaluate the value they offer and whether their current approach will remain relevant as more businesses take direct action to address core issues affecting their carbon footprint.

Companies also need reinvention to ensure they are successful and relevant in the future reality. For example, Germany’s second largest utility, RWE – a provider of electricity and gas for 24 million customers throughout Europe – is reinventing itself from a traditional energy company that develops and operates power plants to a ‘renewable energy service provider’ that helps manage and integrate renewables into the energy grid. Utilizing its infrastructure and other core strengths, RWE is shifting its business model ‘from volume to value,’ according to a recent article from Greentech Media, because “incremental improvement of the existing value chain” is not enough.

We need more businesses, utilities and governments to make this shift from incremental to continuous improvements. Companies must stop ‘aspiring’ to reach long-term goals and, instead, deliver measurable and scalable solutions in the short-term. We need system-wide step change to reverse the abuse and neglect under which we have been operating.

It is time to put everything having to do with practicing business today – from our supply chains to our product (during and after its planned life) to the ways we consume and go about our daily lives – into a centrifuge and spin all the waste, harmful impacts and unsustainable practices out and reconstruct something radically different and radically better. It’s time for a sea change in the way we do business, before the sea changes so alterably that it’s too late.

[1] National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has measured carbon dioxide levels at Mauna Loa, Hawaii for the past 55 years. Although there is consensus on the longer-term predictions, they have not been directly measured.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed